Writing well to get ahead in politics

In his biographical essay ‘Asquith,’ Winston Churchill describes how an ability to write well helped him win swift political advancement in the reforming British Liberal government headed by H.H. Asquith from 1908 to 1915. Churchill entered Asquith’s cabinet as President of the Board of Trade in 1908, at the age of 34; became Home Secretary at 36; and First Lord of the Admiralty – one of the top national security positions in the British Empire – at 37.

In his biographical essay ‘Asquith,’ Winston Churchill describes how an ability to write well helped him win swift political advancement in the reforming British Liberal government headed by H.H. Asquith from 1908 to 1915. Churchill entered Asquith’s cabinet as President of the Board of Trade in 1908, at the age of 34; became Home Secretary at 36; and First Lord of the Admiralty – one of the top national security positions in the British Empire – at 37.

“He [Asquith] was always very kind to me and thought well of my mental processes; was obviously moved to agreement by many of the State papers which I wrote. A carefully-marshalled argument, cleanly printed, read by him at leisure, often won his approval and thereafter commanded his decisive support. His orderly, disciplined mind delighted in reason and design. It was always worth while spending many hours to state a case in the most concise and effective manner for the eye of the Prime Minister. In fact I believe I owed the repeated advancement to great offices which he accorded me, more to my secret writings on Government business than to any impressions produced by conversation or by speeches on the platform or in Parliament. One felt that the case was submitted to a high tribunal, and that repetition, verbiage, rhetoric, false argument, would be impassively but inexorably put aside.”

Is it fair to say that an ability to reason and write well is much less valuable for a political career today than it was a hundred years ago? Or to say that these qualities have usually been less important in the more democratic United States than in aristocratic Europe?

Anyway, Churchill was lucky to have had, in Asquith, a leader himself of sufficient brilliance to appreciate and promote such a talented subordinate. Asquith took a double first in ‘Mods and Greats’ (classical languages and philosophy) at Oxford in 1874, was elected to a prize fellowship at Balliol, and went on to a successful career as a highly paid London lawyer before going into politics.

Churchill gives us this attractive portrait of the man, in the setting of a vanished world:

“I saw him most intimately in the most agreeable circumstances. He and his wife and elder daughter were our guests on the Admiralty yacht for a month at a time in the three summers before the War. Blue skies and shining seas, the Mediterranean, the Adriatic, the Aegean, Venice, Syracuse, Malta, Athens, the Dalmatian coast, great fleets and dockyards - the superb setting of the King's Navy; serious work and a pleasure cruise filled these very happy breathing-spaces…

“For the rest, you would not have supposed he had a care in the world. He was the most painstaking tourist. He mastered Baedeker, examined the ladies upon it, explained and illuminated much, and evidently enjoyed every hour. He frequently set the whole party competing who could write down in five minutes the most Generals beginning with L, or Poets beginning with T, or Historians with some other initial. He had innumerable varieties of these games and always excelled in them… he basked in the sunshine and read Greek. He fashioned with deep thought impeccable verses in complicated metre, and recast in terser form classical inscriptions which displeased him. I could not help much in this. But I followed with attention the cipher telegrams which we received each day, and of course we were always on the new wireless of the Fleet.

“One afternoon we drove along a lovely road near Cattaro - a harbour in those days of peculiar interest, not merely for its scenery. We suddenly met endless strings of mules and farm horses. We asked where they were going and what for. We were told, 'They are dispersing. The manoeuvres are cancelled.' The Balkan and European crisis of 1913 was over!”

days of peculiar interest, not merely for its scenery. We suddenly met endless strings of mules and farm horses. We asked where they were going and what for. We were told, 'They are dispersing. The manoeuvres are cancelled.' The Balkan and European crisis of 1913 was over!”

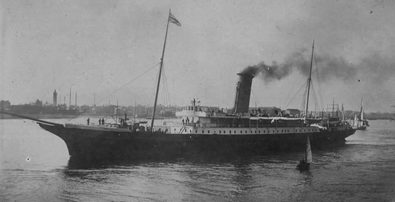

(The first picture is the Admiralty yacht ‘Enchantress’. The second is a view of Cattaro (Kotor), a coastal town in Montenegro, one of the main bases of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in World War I.)